Open Government

Open government! It sounds like an obvious idea to most Americans. Who would want closed government? The battle-tested people who wrote and ratified the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights knew about the heavy boot of a government that could operate in secret and make decisions without public knowledge or input. They fought the Crown and its Redcoats and won. That set the stage for something new and gave us a set of rules to define what government could do: the balance of powers, election rules, making treaties, etc. Then they ratified the first ten amendments to define what government could not do. We would have free speech, press and religion, no searches of our property without a court order, fair public trials, and the rest. The press was included to act as a “watchdog” on the official branches, to be the eyes and ears for the public so it could know what government was doing. Without that public knowledge, the Founders feared excessive government power could evolve into tyranny.

When there are attempts to infringe on our right to know what government is up to, all of us need to be concerned, no matter what the intentions.

To protect these rights the population needs to be vigilant.

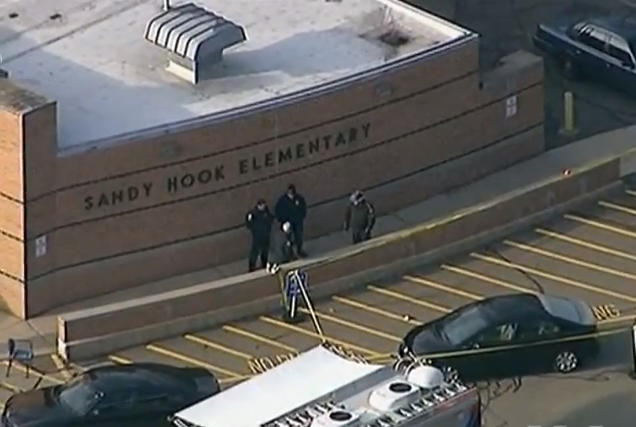

Prosecutors, legislators, police and citizens sometimes try to reduce the openness of government in the name of secrecy, to protect “proprietary” information, or, following the deaths in Newtown, in the name of privacy.

Let’s be clear: The massacre at Sandy Hook was beyond awful. The university at which I teach had ties to four of the six teachers slaughtered. To think of the children, whose lives were cut so short, brings sadness that can’t be measured.

But to reduce the public’s right to know about what government does, or does not do, in the name of privacy rights for the victims and survivors is shortsighted. It ignores our rich history and the Freedom of Information Act’s attempt to make sure all levels of government are open to public scrutiny.

We don’t know many things about what happened at Sandy Hook. Clearly, we need to know more about Adam Lanza and his mother. We need to know more about mental health and access to guns. We also need to know the specifics about what happened in that school as fully as possible. We are prevented from seeing the crime scene photos because “someone might misuse them on the internet.” But crime photos have been released for many years. Why should the threat of some possible future misuse prevent the public from access to material that would be used in a court? It’s important to know who took the photos. What were the angles? Are there facts in the pictures that might help us understand and reduce the chance of other such acts of violence in schools? Of course, most journalists would not publish these photos because they would be disturbing, but they are part of the official record to which the public has long had access.

What about the 911 calls? Other such calls have been released regularly since they were first recorded and the public has heard many of them. Why are they recorded in the first place? It’s to improve response time, to check whether the dispatchers, who are government employees, did their jobs well, and to help understand what happened.

These are not trivial things. Without such public distribution, records can be altered. We like to think prosecutors, police and politicians will do the right thing. Most of the time, they do. But we know that evidence has sometimes been ignored, or manipulated and used for a variety of motives, often to protect those with power, or for some social or political gain. Open government is designed, specifically, to reduce such potential abuse.

There is a certain patronizing attitude in this drive to hold back public records from our view. It treats the public as if we are all children. It seems to argue that the public, in a democracy, can’t be trusted with reality. Those who want to keep these materials from the public are also saying: “Trust the government.” Trust, as Ronald Reagan said, needs to be verified. That’s why public officials should operate with real openness so citizens can, indeed, verify.

The ugliness of Sandy Hook, and many other crimes in our long history, should not become a step on the “slippery slope” that erodes open government and our democratic history and ideals.

Recent Comments